(Background Music ~ Adrian von Ziegler)

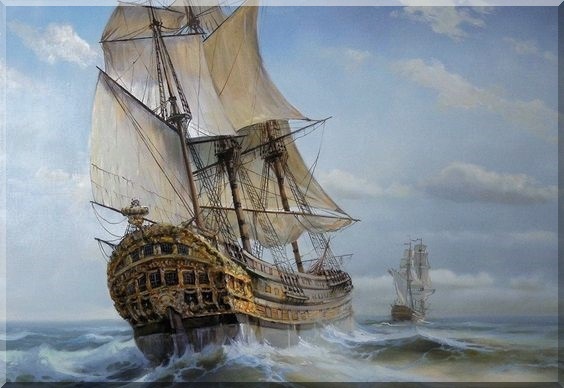

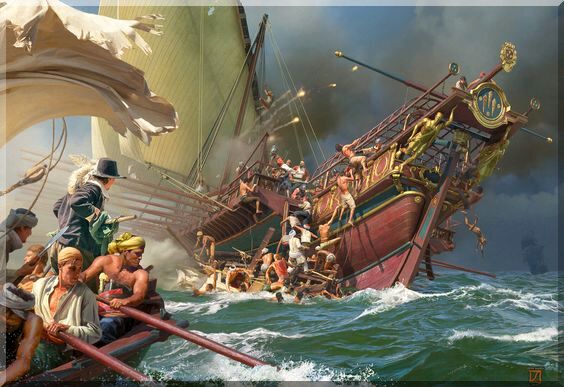

Pirate Ships The single-masted sloop had a bowsprit almost as long as her hull making her perhaps one of the swiftest vessels of her day. If the wind was favorable, a square topsail could be hoisted to give her a top speed that could on occasion exceed eleven knots. The Sloop was a favourable ship for pirates and smugglers alike. This relatively small vessel could carry around 75 pirates and around ten cannons. The Sloop was often the ship of choice for hunting in the shallower channels and sounds. The Schooner which came into widespread use around the last half of the eighteenth century is a little of all of the best features in a pirate ship. Perhaps her greatest virtue lie in her shallow draft. She was favored by pirates of the North American coast and the Caribbean. Fully loaded she was still small enough to navigate the shoal waters and to hide in remote coves. The Schooner could also reach 11 knots in a good wind. Another versatile ship the Brigantine was more of a captain's ship for a pirate. This was generally a 150 ton, 80 foot vessel that could carry around 100 pirates mounting over 10 cannons with a cargo space about twice as big as the sloop. She had two masts. Her main sail could be fitted with either square sails that were best in quartering wind, or fore-and-aft sails for sailing windward. This larger ship was the clear choice for battle or combat rather than the quick, hit and run type piracy tactics that were practiced with the smaller sloops and schooners. It was also rugged enough to cross the Atlantic ocean, and faired better in harsh sea conditions. Also keep in mind that pirates could not build a ship to order like the merchants and military did. They had to be opportunists and having looted a ship, the pirates would either burn the vessel, let it go on it's way, set it adrift, or take the ship over for their own use. Most pirate ships were no more then captured vessels taken as prizes and then altered to suit the pirates needs. The large three-masted squarerigger type ships could be fitted with well over twenty cannon plus many swivel guns and a crew of around two hundred or more men. She could make a formidable adversary and an excellent flagship for a large group of pirates despite her lack of agility. Many ships would probably have surrendered to her without a shot fired if they were not fast enough to out-sail her. Besides being greatly feared and comparable to a Navy Frigate, she had a reputation for seaworthiness on long voyages and a cargo space about twice as large as that of the brigantine. One of the most impressive aspects of some of the early eighteenth century pirates is the enormous voyages which they made in search of riches. They sailed the North American coast from Newfoundland to the Caribbean. They crossed the Atlantic to the Guinea coast of Africa. And they rounded the Cape of Good Hope to Madagascar in order to plunder the ships in the Indian Ocean. The Barbary corsairs of the Mediterranean mainly used oar powered galleys rowed by slaves. These were long rather slender craft which were renowned for their speed, and sailing ships traveling in the calm winds of the Mediterranean were at their mercy. Their oars made them very quick, enabling them to maneuver quite easily and to come alongside an intended victim. When the winds picked up the corsairs hoisted a large lateen sail on a single mast amidships. The galleys were armed with one or more big guns at the bow, and several swivel guns were also mounted along the side rails. But like with most pirate ships their main weapon was in their fighting crews, who could number over one hundred men on a large galley. These men would quickly swarm aboard a ship and sweep aside all opposition. These corsairs were not generally involved in piracy for gold or silver. They were trying to capture people, who they could hold for ransom, use as oarsmen on their galleys, or just sell as slaves.

Of the many types of ships used in the great age of sail. Most of them are distinguished by their rigging, hull, keel, or number and configuration of masts. Designs would usually be modified over the course of time with lessons gained from use. The same ship type could vary in how it was built by country. Pirates sailed aboard almost all of the ship types listed below. Various small sailboats and fishing boats were not included.

Ship Classes BARK (BARQUE) Before the 1700's the name was applied to any small vessel. Later it applied to a small ship having three masts. The first two being square-rigged, and the third ( aft mast ) being fore-and-aft rigged. Fast ship with shallow draft. Favorite of Caribbean pirates. Crew around max. of 90. BRIG Very popular in the 18th and early 19th centuries. A brig is a sailing vessel with two square-rigged masts. To improve maneuverability, the aft mast carries a small gaff rigged fore-and-aft sail. The brig actually developed as a variant of the brigantine. Re-rigging a brigantine with two square-rigged masts instead of one gave it greater sailing power, and was also easier for the crew to manage. During the Age of Sail, brigs were seen as fast and maneuverable and were used as both naval warships and merchant vessels. When used as small warships, they carryed about 10 to 18 guns. Due to their speed and maneuverability they were also popular among pirates, although they were rare among American and Caribbean pirates. BRIGANTINE Originally the brigantine was a sail and oar driven small warship used in the Mediterranean in the 13th century. It was lateen rigged on two masts and had between eight and twelve oars on each side. Its speed, maneuverability and ease of handling made it a favorite of the Mediterranean pirates. Its name is derived from the Italian word brigantino, meaning brigand. By the 17th century the term was adapted by Atlantic maritime nations. The word eventually was split into brig and brigantines. Each word meaning a different class of ship. The brigantine had no lateen sails but was instead square-rigged on the foremast and had a gaff-rigged mainsail with square rig above it. The main mast of a brigantine is the aft one. The brigantine was generally larger than a sloop or schooner but smaller than a brig. CARAVEL A small ship meant for trading. Originally lateen-rigged they later developed into square-masted ships and were used by the Spanish and Portuguese for exploration. Around 80 feet long. CARRACK Before the advent of the galleon, carracks were the largest ships. They often reached 1,200 tons. They were used for trading voyages to India, China, and the Americas by the Spanish and Portuguese. They were 3 masted with square sails on the fore and main masts and lateen-rigged on the mizzen. They had very high fore and aft-castles. She carried an immense amount of power and thus was able to easily fend off pirates. Only through surprise could one hope to take one of these towering giants. CLIPPER A very fast sailing ship of the 19th century that had three or more masts and a square rig. They were generally narrow for their length, had a large total sail area, and could carry limited bulk freight. These ships came to be recognized for there great speed rather than cargo space. There speed was crucial to compete with the new steamships for commercial use. China clippers are the fastest commercial sailing vessels ever made. Clipper ships were mostly constructed in British and American shipyards. They sailed all over the world, primarily on the major trade routes of the era. The ships had short expected lifetimes and rarely outlasted two decades of use before they were broken up for salvage. Although they were built a century after the golden age of piracy, given their speed and maneuverability, clippers frequently mounted cannon or carronades and some were used for piracy, privateering, smuggling, and interdiction service. CORVETTE (CORVET) The term corvette seems to have begun with the French Navy in the 1670s, to describe a small, maneuverable, lightly armed warship, smaller than a frigate and larger than sloops-of-war. Most sloops and corvettes of the late 17th century were around 40 to 60 feet in length. They carried four to eight small guns on a single deck. These early corvettes grew quickly in size over the decades, and by the 1780s they reached lengths of over 100 feet. Most of these large versions had three masts, and carried about 20 guns. The British Navy did not adopt the term until the 1830s, to describe a small sixth-rate vessel somewhat larger than a sloop. CUTTER Cutters were widely used by several navies in the 17th and 18th centuries and were usually the smallest commissioned ships in the fleet. A cutter is a small single-masted boat, fore-and-aft rigged, with two or more headsails, usually carried on a very long bowsprit, which was sometimes as long as half the length of the boat's hull. The mast may be set farther back than on a sloop. The rig gave the cutter excellent maneuverability and they were much better at sailing to windward than a larger square rigged ship. Later larger naval cutters often had the ability to hoist two or three square-rigged sails from their mast to improve their downwind sailing performance as well. Over time the cutter grew in size to include ships of two and three masts. Pilot cutters were widely used near ports to ferry harbor pilots to the big ships. Navies used cutters for coastal patrol, customs duties, escort, carrying personnel and dispatches and for small 'cutting out' raids. As befitted their size and intended role naval cutters were lightly armed, often with between six and twelve small cannon. DHOW Dhows were meant to be trading ships, having a single mast which was lateen-rigged. They were from 150 to 200-ton ships. Arab pirates arming her with cannon would use these ships. DUTCH FLUTE (FLEUT) An early 17th century merchant ship, similar in design to a bark (barque). These were inexpensive to build, and could carry a large cargo. EAST INDIAMAN Designed out of the experiences gathered from long and arduous voyages to india. This class of ships were one of the largest merchant vessels of there era, having three masts and weighing 1100 to 1400 tons. Built from the early 1600's to the end of the 1700's, to transport goods between Asia and Europe. They were usually well armed with cannons to defend themselves. FRIGATE The Venetians called a frigate a small oared boat around 35 feet in length and around 7 feet wide. The English adopted the word for a larger ship which may have carried oars. Around 1700, the English limited the word to mean a class of warship which was only second in size to the Ship-of-the-Line (Man-O-War). Frigates were three-masted with a raised forecastle and quarterdeck. They had anywhere from 24 to 38 guns, and were faster than the ship-of-the-lines. Frigates were used for escort purposes, and sometimes to hunt pirates. Only a few pirates were ever in command of a frigate as most would flee at the sight of one. FUSTE (FUSTA) A favorite of Barbary Corsairs, it was a small ship with both sail and oars. It was fast, long and had a low profile. GALIOT (GALLIOT) Mediterranean In the 16th century, a galiot was a type of ship with oars, also known as a half-galley. The Galiot was long, and sleek with a flush deck. Then, from the 17th century forward, a ship with sails and oars. As used by the Barbary pirates against the Republic of Venice, a galiot had two masts and about 16 ranks of oars. Warships of the type typically carried between two and ten cannons of small caliber, and between 50 and 150 men. She was used by the Barbary corsairs in the Mediterranean. GALIOT (GALLIOT) North Sea In the 17th thru 19th century, a galiot was a type of Dutch or German trade ship, similar to a ketch, with a rounded fore and aft like a fluyt. They had nearly flat bottoms to sail in shallow waters. These ships were especially favored for coastal navigation in the North Sea and Baltic Sea. GALLEON Galleons were large ships meant for transporting cargo. Galleons were sluggish behemoths, not able to sail into or near the wind. The Spanish treasure fleets were made of these ships. Although they were sluggish, they weren't the easy target you would expect for they could carry heavy cannon which made a direct assault upon them difficult. She had two to three decks. Most had three masts, forward masts being square-rigged, lateen-sails on the mizzenmast, and a small square sail on her high-rising bowsprit. Some galleons sported 4 masts but these were an exception to the rule. GALLEY Galleys have an extremely long history, dating back to ancient times. They were used until the Russo-Swedish war of 1809. They had one deck and were mainly powered by oars. They were costly to maintain and fell into disuse. However they were still being used by the Barbary corsairs in the Mediterranean. As they were meant to carry soldiers they were used in a few large-scale raids. There was a version of the galley used in the Atlantic by the English. They had a flush deck and were propelled by both oar and sail. They were rigged like frigates. Captain Kidd made his name in one of these, the "Adventure Galley". GUINEAMAN A guineaman was a large cargo ship engaged in trade with the Guinea coast of Africa. Many were specially converted or purpose built for the transportation of slaves, especially newly purchased African slaves to the Americas. Their hulls were divided into holds with little headroom, so they could transport as many slaves as possible. Unhygienic conditions, dehydration, dysentery and scurvy led to high mortality rates on average 15% and up to a third of captives. Slave ships adopted quicker, more maneuverable forms to cross the Atlantic faster to increase profits, and later to evade capture by naval warships once the African slave trade was banned by the British and Americans in 1807. The guineaman's speed and size made them attractive ships to repurpose for piracy, and also for naval use after capture. The USS Nightingale(1851) and HMS Black Joke(1827) were examples of such vessels. Several well known pirates like Blackbeard and Samuel Bellamy captured and converted them for piracy. JUNK The word junk derives from the Portugues junco, which in turn came from the Javanese word djong, which means ship. The ship has a flat-bottom with no keel, flat bow, and a high stern. A junk's width is about a third of its length and she has a rudder which can be lowered or raised providing excellent steering capabilities. A junk has two or three masts with square sails, made from bamboo, rattan or grass. Contrary to belief, the junk is capable of operating in any seas as she is a very sea-worthy vessel. KELCH A two mast vessel with a large sail on the mainmast and a smaller mizzen. Historically the ketch was a square-rigged vessel, most commonly used as a freighter or fishing boat in northern Europe, particularly in the Baltic and North seas. During the 17th and 18th centuries, ketches were commonly used as small warships. In the latter part of the 18th century, they were largely supplanted by the brig, which differs from the ketch by having a forward mast smaller (or occasionally similar in size) than the aft mast. The ketch continued in use as a specialized vessel for carrying mortars until after the Napoleonic wars, in this application it was called a bomb ketch. In modern usage, the ketch is a fore-and-aft rigged vessel used as a yacht or pleasure craft. LONGBOAT Much like a rowboat except they were very long. These were carried on ships and used for coming and going to the ship. They were normally rowed but often had a removable mast and sail. Also some were armed with one or more very small cannon. LUGGER A vessel with a lugsail rig, normally two-masted. When they were used for smuggling or as privateers, extra sail was often added aft. These small ships were mainly used by merchants in coastal waters. PINK (MERCHANT) There are two classifications of Pink. The first was a small, flat-bottomed ship with a narrow stern. This ship was derived from the Italian pinco. It was used primarily in the Mediterranean as a cargo ship. In the Atlantic the word pink was used to describe any small ship with a narrow stern, having derived from the Dutch word pincke. They were generally square-rigged and used as fishing boats, merchantmen, and warships. PINNACE The Dutch built pinnaces during the early 17th century. They had a hull form resembling a small "race built" galleon, and were usually square rigged on three masts, or carried a similar rig on two masts, like the later "brig". Pinnaces were used as merchant vessels, privateers and small warships. SCHOONER The Schooner has a narrow hull, two masts and is less than 100 tons. She is generally rigged with two large sails suspended from spars reaching from the top of the mast toward the stern. Other sails sometimes were added, including a large headsail attached to the bowsprit. She had a shallow draft which allowed her to remain in shallow coves waiting for her prey. The Schooner is very fast and large enough to carry a plentiful crew. It was a favorite among both pirates and smugglers. SHIP OF THE LINE (MAN-O-WAR) From the 17th century into the 19th, these ships were the "heavy-guns" of the naval fleet. At first they resembled galleons in design, but carried awesome firepower with an average of 60 guns. Over the course of time, they developed into larger and heavier beasts. They were designed to be large enough for use in line of battle tactics, hence there name. In the 18th century they ranged from fourth rate ships of 50 guns, up to first rate ships of 100 guns. Most were around 1,000 tons and had 3 masts, which were square-rigged, except for a lateen sail on her aft-mast. Only the three major sea-powers of the time (Spain, England, and France) had an extensive use of these ships. SLAVE SHIP (SLAVER) These were large cargo ships converted for the purpose of transporting slaves. They reached there peak use between the 17th to early 19th century. There large size and ability to handle long ocean voyages made them attractive targets for pirates. Early western slave ships would have mostly been square rigged merchant/galleon types. Later these ships became more purpose built. See Guineaman description above. SLOOP The Sloop was fast, agile, and had a shallow draft. They usually had a speed of around 12 knots. Her size could be as large as 100 tons. She was generally rigged with a large mainsail which was attached to a spar above the mast on its foremost edge, and to a long boom below. She could sport additional sails both square and lateen-rigged. She was used mainly in the Caribbean and Atlantic. Since piracy was a significant threat in Caribbean waters, merchants sought ships that could outrun pursuers. Ironically, that same speed and maneuverability made them highly prized and even more targeted by the pirates they were designed to avoid. SLOOP-OF-WAR In the 18th and most of the 19th centuries, a sloop-of-war in the British Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. A sloop-of-war was quite different from a civilian or merchant sloop, which was a general term for a single mast vessel rigged like what would today be called a gaff cutter. In the first half of the 18th century, most naval sloops were two mast vessels, usually carrying a ketch or a snow rig. A ketch had main and mizzen masts but no foremast, while a snow had a foremast and a main mast but no mizzen. The first three mast sloops-of-war appeared during the 1740s, and from the mid-1750s on most were built with three masts. The longer decks of the multi-mast vessels also had the advantage of allowing more guns to be carried. In the 1770s, the two mast brig sloop became popular with the British Navy as it was cheaper and easier to build and for crews to sail it. SNOW A snow or snaw was a type of brig often referred to as a snow-brig. It was typically a merchant vessel, but was a common form of sailing rig for small two-masted sloops, especially during the first half of the eighteenth century. Snows carried square sails on both masts, but had a small trysail mast, sometimes called a snowmast, stepped immediately abaft the mainmast. XEBEC (CHEBEC or SHEBEC) The xebec was favoured among Barbary pirates for she was fast, stable and large. They could reach 200 tons and carried from 4 to 24 cannon. In addition she carried from 60 to 200 crewmen. The xebec had a pronounced overhanging bow and stern, and three masts which were generally lateen-rigged. In addition to sails she was rowed.

Pirate Ship Crews Today there are many different misconceptions and myths about buccaneers throughout history. A common misconception made by many people is in the role and authority of the pirate captain. Unlike naval captain's who were appointed by their respective governments and who's authority was supreme at all times. Most pirate captain's were democratically elected by the ships crew and could be replaced at any time by a majority vote of the crewmen. For example some captains were voted out and removed for not being as aggressive in the pursuit of prizes as the crew would have liked. And others were abandoned by their crews for being alittle to bloodthirsty and brutal. Several were even murdered by their own men. They were expected to be bold and decisive in battle. And also have skill in navigation and seamanship. Above all they had to have the force of personality necessary to hold together such an unruly bunch of seamen. This left the captain of most pirate ships in a rather precarious position and some were in truth little more then a figurehead. Generally speaking, he was someone the crew would follow if he treated them well, maintained their respect, and was a fairly successful booty hunter... but, could be replaced if enough of the men lost confidence in him and felt he wasn't performing his duties as well as he should. However, despite all this the captain was frequently looked upon with respect as a knowledgable leader of men. And the pirate crews historically appeared to have followed his judgement in most matters. There are surprisingly few detailed descriptions of what the pirate captains looked like, and those we do have are rarely flattering. Most seem to have adopted the clothes of naval officers or merchant sea captains, which in this period followed the style of English gentlemen. QUARTERMASTER During the Golden Age of Piracy, most British and Anglo-American pirates delegated unusual amounts of authority to the Quartermaster who became almost the Captain's equal. The Captain retained unlimited authority during battle, but otherwise he was subject to the Quartermaster in many routine matters. The Quartermaster was elected by the crew to represent their interests and he received an extra share of the booty when it was divided. Above all, he protected the Seaman against each other by maintaining order, settling quarrels, and distributing food and other essentials. Serious crimes were tried by a jury of the crew, but the Quartermaster could punish minor offenses. Only he could flog a seaman after a vote from the Crew. The Quartermaster usually kept the records and account books for the ship. He also took part in all battles and often led the attacks by the boarding parties. If the pirates were successful, he decided what plunder to take. If the pirates decide to keep a captured ship, the Quartermaster often took over as the Captain of that ship. SAILING MASTER or NAVIGATOR This was the officer who was in charge of navigation and the sailing of the ship. He directed the course and looked after the maps and instruments necessary for navigation. Since the charts of the era were often inaccurate or nonexistent, his job was a difficult one. It was said a good Navigator was worth his weight in gold. He was perhaps the most valued person aboard a ship other than the Captain because so much depended upon his skill. Many Sailing Masters had to be forced into pirate service. Some were elected by the crew to serve as Captain. Several pirate Captain's also performed the duties of Sailing Master when needed. BOATSWAIN The Boatswain supervised the maintenance of the vessel and its supply stores. He was responsible for inspecting the ship and it's sails and rigging each morning, and reporting their state to the Captain. The Boatswain was also in charge of all deck activities, including weighing and dropping anchor, and the handling of the sails. CARPENTER The Carpenter was responsible for the maintenance and repair of the wooden hull, masts and yards. He worked under the direction of the ship's Master and Boatswain. The Carpenter checked the hull regularly, placing oakum between the seems of the planks and wooden plugs on leaks to keep the vessel tight. He was highly skilled in his work which he learned through apprenticeship. Often he would have an assistant whom he in turn trained as a Carpenter. MASTER GUNNER The Master Gunner was responsible for the ship's guns and ammunition. This included sifting the powder to keep it dry and prevent it from separating, insuring the cannon balls were kept free of rust, and all weapons were kept in good repair. A knowledgeable Gunner was essential to the crew's safety and effective use of their weapons. MATE On a large ship there was usually more than one Mate aboard. The Mate served as apprentice to the Ship's Master, Boatswain, Carpenter and Gunner. He took care of the fitting out of the vessel, and examined whether it was sufficiently provided with ropes, pulleys, sails, and all the other rigging that was necessary for the voyage. The Mate took care of hoisting the anchor, and during a voyage he checked the tackle once a day. If he observed anything amiss, he would report it to the ship's Master. Arriving at a port, the mate caused the cables and anchors to be repaired, and took care of the management of the sails, yards and mooring of the ship. SAILOR The common sailor, which was the backbone of the ship, needed to know the rigging and the sails. As well as how to steer the ship and applying it to the purposes of navigation. He needed to know how to read the skies, weather, winds and most importantly the moods of his commanders. Other jobs on the ships were surgeon (for large vessels), cooks and cabin boys. There were many jobs divided up amongst the officers, sometimes one man would perform two functions. Mates who served apprenticeships were expected to fill in or take over positions when sickness or death created an opportunity.

Historical Pirate Ships

Ships Figurehead The Phoenicians not only adopted the primitive eye motif for their trading vessels at an early date, they later adorned the prows of their galleys with carved wooden likenesses of deities, animals, birds,and serpents. The Greeks also adopted the eye motif, as surviving decorations on ther pottery vases prove. The prow adornments of the vessels of the ancient world grew increasingly more complicated. Athenian naval vessels of the classical era were frequently adorned with full-length wooden carvings of Athena, the goddess for whom the city is named. When Rome took over dominance of the Mediterranean, its warships and galleys were decorated with fierce prow fires drawn from its own pantheon, an assertion proven by surviving scultpures dating from Rome's imperial heyday. The Carthaginians, Rome's most serious early rivals, used carved figures of the god Ammon Jupiter to head up their warships. The figureheads of these ancient people were linked to the superstition that these sculptered images were guardians of the vessels they adorned and were also supposed to frighten enemies, as well as give a religious significance to the exploits in which they were engaged. The same motive was later endorsed by the Vikings, Danes and Normans during the early Christian era. The prows of vessels in which these cultures engaged in their far-flung operations rode high out of the water and were frequently tipped with intimidating dragons, sea serpents of fierce animal heads. Since the Vikings are credited with having been the first navigators to explore North American waters, it is likely that the figureheads on their vessels were the first ones to appear in the New World. The sailors of these early northern European vessels firmly believed that their wooden icons were endowed with magical powers. Seafarers of later eras turned their backs on this type of idol worship, but remained fiercely superstitious concening the protection of the figureheads on their vessels, believing that any damage to these icons meant certain disaster. Shipbuilding, both for mercantile and military purposed, remained fairly static until the Renaissance, between 1400 and 1600, when nations and city-states throughout Europe began vying for natutical supremacy. At that time, England, France, Spain, Portugal and Holland, as well as the Italian city-states of Genoa and Venice, began jockeying for power, and the increasingly lavish and sophisticated vessels that were launched from their dockyards continued to stress the importance of intimidating figureheads. This assertion can easily be supported by referring to the countless seascapes, drawings, engravings and other iconographic evidence that played an important part in the artistic output of the same nations and city-states at that time. Catholic countries and city-states frequently adorned the prows of their great gallons and merchantmen with religious figures. Of particular note were the vessels of the Spanish Armada, the great fleet of warships dispatched in 1588 by Philip II of Spain to subdue Protestant England and return it to the fold of the Catholic faith. Surviving paintings, drawings, engravings and tapestry depicting the action show that most of the Spanish galleons had elaborate prow decorations that depicted Christ and the Virgin Mary, as well as numerous popular saints whose invocations to the Almighty on behalf of the Catholic cause, it was thought, would guarantee an overwhelming victory to the Spanish enterprise. As for the prow decorations of the small English ships that eventually spelled defeat for King Philip's mighty galleons, their stemheads, according to surviving iconographic sources, were singularly bare of ornamental carvings. But that does not mean that the English warships of the same period were without elaborate figureheads and other carvings. For instance, Sir Francis Drake made the first English circumnavigation of the globe in a vessel that sported a gilded deer on its prow, thereby causing the ship to be named the Golden Hind. Later, during the reign of Charles I, English ship carpenters and wood carvers created the Sovereign of the Seas, one of the most highly decorated vessels in the history of shipbuilding. Graced with a ferocious gilded lion at its stemhead, it and the other carving and gilding of this fabulous vessel cost around 7,000 British pounds, quite a sum considering the total cost of the vessel was around 40,000 pounds. Up until the middle years of the 18th century, the figurehead was the crowning wooden adornment on any warship or important mercantile vessel. Though figureheads increasingly became less decorative as time went on, that did not mean that the men who sailed the ships ceased feeling that the wooden sculptures on the prows were more than merely ornamental. For instance, there are numerous records concerning how the figureheads of new vessels were consecrated by the superstitious with hefty splashes of wine to guarantee that they would give the vessels good luck when they were "launched into their element"--to quote a widely used nautical term of the period. . Thus came the golden age of figureheads, which lasted from around 1790 to 1825. That's when most of the warships and merchant vessels of Europe and North America sported elaborate prow adornments The high water mark of figureheads was reached during the clipper-ship era dating from the early and middle years of the 19th century. The graceful bows of these streamlined ships presented an excellent opportunity to display figureheads to their best advantage. By the late 19th century, however, figureheads on most vessels gave way to simpler and less expensive billet heads (i.e. scrollcarvings resembling the end of a violin). This change took place because the carvings were expensive and easily damaged, either by rough weather or in battle. In this way, a tradition extending backward to the ancient Chinese and Egyptians has run its colorful course.

Related Resources for Pirate Ships * Famous Pirate Ships - Facts and Information on the Subject. * Famous Pirate Ship Names - From piracys Golden Age. * 7 Famous Pirate Ships - Brief bit of information on each ship. * 10 Fearsome Ships From The Golden Age Of Piracy - Hauntingly interesting. * Ship and Sailing Information - Good General Sailing Resource. The Great Ships Series - The Frigates

Page best viewed with a 1080px width. Copyright 2000-2025 Brethren of the Coast. All Rights Reserved. |